Neurosurgery

Eye in the brain

Orbital injury with secondary involvement of the brain is a potentially serious condition demanding urgent surgical repair. Neglected injuries may present with complications leading to significant morbidity such as cerebrospinal fluid orbitorrhoea, tension pneumocephalus, carotid cavernous fistulas, intracranial hematoma, subperiosteal orbital hematoma, orbital encephalocele, blepharocele, and vision loss.However, posttraumatic globe herniation inside anterior cranial fossa is an unreported complication, which would need immediate repair.

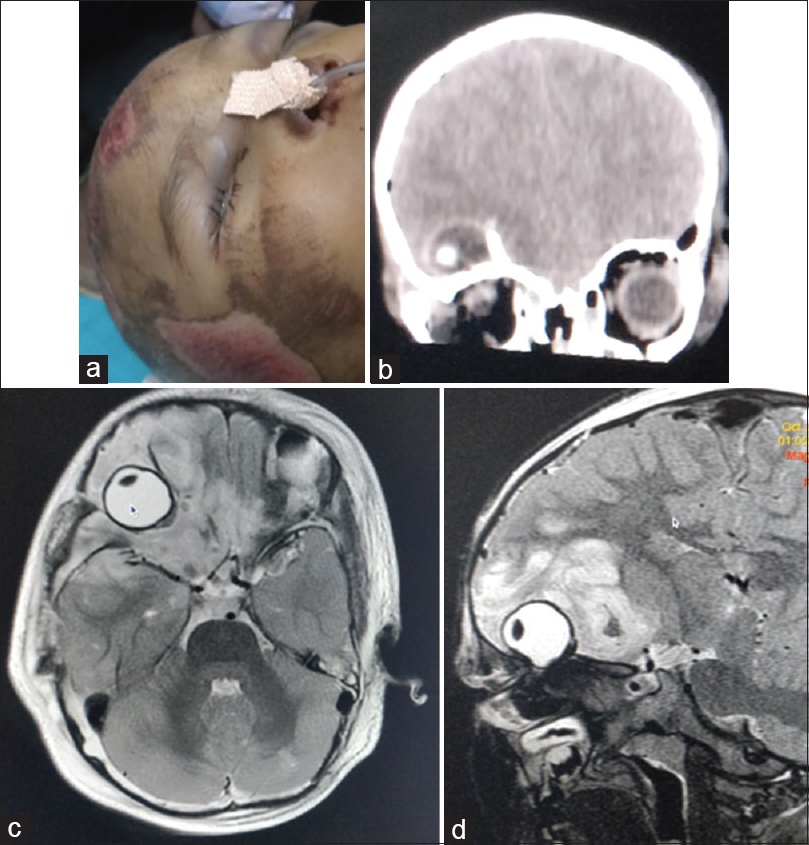

A 5-year old girl was brought to the emergency department following a road traffic accident. On examination, she was drowsy and did not cooperate for visual evaluation because of painful periorbital edema. CT scan of the head revealed right orbital roof fracture with complete herniation of eyeball inside the anterior cranial fossa beneath the right frontal lobe with significant periglobal edema. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed the herniated eyeball injury to the right optic nerve. The parents did not consent for a transcranial surgery despite being explained the risks and prognosis of the conservative management and left against medical advice.

Not a refugee, nasogastric tube in the brain: Modes of prevention and controversies in management

Nasogastric tube (NGT) intubation is one of the most commonly performed bedside procedures for enteral feeding and for emptying gastric contents. Though considered an innocuous procedure, vigorous forceful attempts at NGT insertion may lead to various life-threatening complications, viz. esophageal perforation, bronchopleural fistula, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, and pulmonary hemorrhage. Among these complications, iatrogenic insertion into the brain is the one most lethal. Martinelle et al., first reported this complication in 1974 in a patient of head injury.

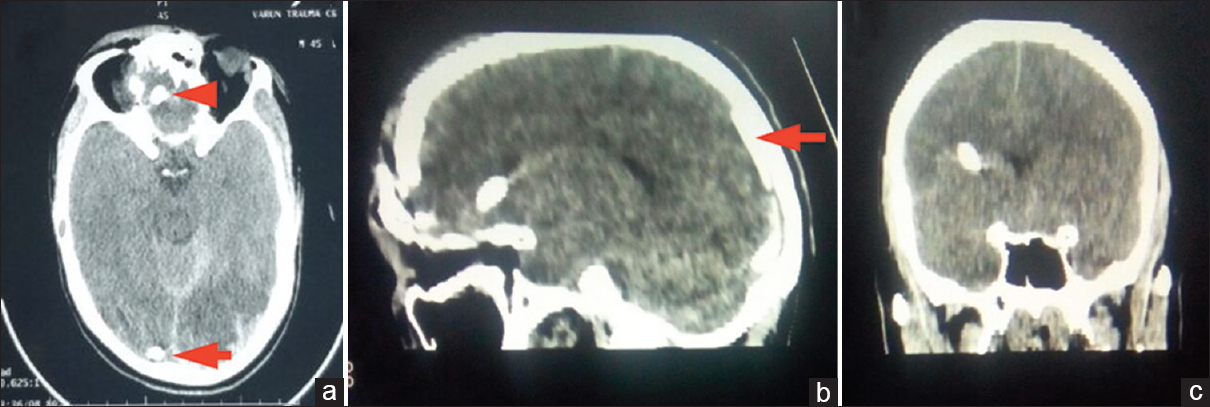

A 45-year old male patient was referred in an unconscious status (the Glasgow Coma Scale Score [GCS]: Eye opening 2; Verbal response: 2; Motor response: 5) following an explosive blast injury. The patient was primarily managed at a health care centre, where endotracheal intubation and NGT insertion were performed. After his initial stabilization, a noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan head was performed to evaluate for associated injuries.

The CT scan of the head revealed a right frontal bone depressed fracture and anterior skull base fracture with bilateral occipital lobe contusions. Sagittal and coronal CT images showed that the NGT had crossed the fractured cribriform plate and had reached the vertex, traversing through the brain parenchyma, masquerading as an acute subdural hematoma or a foreign body. After hemodynamic stabilization, the NGT was gently pulled out from the nose without any complication. There was no cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea or herniating brain matter from the nose. The patient was kept on prophylactic intravenous antibiotic for 1 week. At a 1-month follow-up, the patient had regained consciousness without having any added neurological deficits.

(a) NCCT axial image showing the nasogastric tube traversing the cribriform plate (arrow head), with its the distal end near the occipital area (arrow);

(b) sagittal image, showing the distal end of the tube along the calvaria, masquerading as an acute subdural hematoma (arrow); and,

(c) the coronal image, showing the tube in the brain, visualized as a foreign body. (NCCT; noncontrast computed tomography)

NGT misplacements usually occur in patients with a traumatic head injury following an anterior skull base fracture or after complex craniofacial injuries. Such accidents are secondary to lack of adequate radiological investigations at peripheral primary health centers, and also due to the lack of knowledge on the part of the caregivers. The ‘red flag’ signs of anterior skull base fractures are cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea, herniating brain matter, pneumocephalus, or the presence of internal compound fractures. Aspirating gastric contents or auscultating the “pseudo-confirmation gurgle,” (which may often yield a false positive result) can clinically evaluate the proper placement of an NGT. Other confirmatory measures might be an oral intubation, a nasogastric intubation under fluoroscopic or under direct vision. There can be four possible corridors by which the NGT can enter intracranially – a skull base fracture extending across the cribriform plate, a comminuted fracture involving the floor of the anterior cranial fossa, the cribriform plate being thinned out by previous infections, and/or raised intracranial pressure that may cause bony erosion of the anterior cranial fossa. The presence of a deviated nasal septum or pneumatized air sinuses, and overzealous attempts in an uncooperative patient may favor the false passage of the NGT to remote locations in the brain. Such events can be avoided by establishing a proper clinicoradiological diagnosis of the existence of an anterior skull base fracture. The radiological markers of an anterior skull base fracture have been classified as: type 1, cribriform plate fractures, which occur linearly through the cribriform plate; type 2, fronto-ethmoid fractures, which are fractures of the ethmoid and medial frontal sinus walls; type 3, lateral frontal fractures which are fractures that occur through the lateral frontal sinus to the superomedial wall of the orbit; and, type 4, mixed fractures, which are a combination of any of the fractures from the above categories. Radiological confirmation of the correct placement of the NGT is mandatory before starting enteral feeding. In our case, the underlying etiology responsible for the improper positioning of the NGT was the fracture of cribriform plate.

Optimal management following the intracranial placement of the NGT is controversial. Case reports have mentioned a manual retrieval performed through the nose; or, a segmental removal has been carried out after a craniotomy. A craniotomy with anterior skull base repair may occasionally be required in view of the skull base defect. Apart from introducing infection, intracranial insertion of the NGT might be associated with severe debilitating complications such as the occurrence of an intracranial hematoma, motor or sensory deficits, meningitis, or even death in up to 64% of the cases. Whether a prophylactic antibiotic should be administered remains controversial as there is no literature support for the same; however, as the inserted object is traversing through the nasal cavity in a setting of acute injury, there are chances for the development of an ascending infection alongside the tube. It is practically impossible to get an answer for this query in the near future due to the rarity of this complication. Our case highlights the need to be vigilant during NGT intubation in patients who have suffered from a skull base fracture as a result of traumatic brain injury.